’HeLa’ cell story has real life impacts

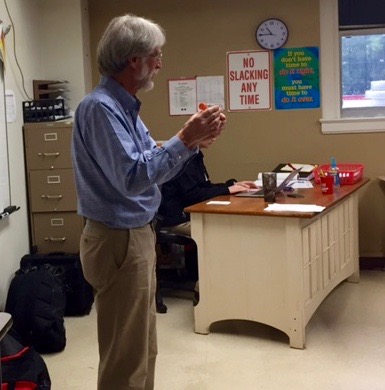

Dr. Brian Storrie, physiology and biophysics professor at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock, holds a vial of “HeLa” cells as he explained the concept in a class discussion at Hope High School about the factual basis for the book “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks”. – Ken McLemore/Hope Public Schools

HOPE – The story of a woman who has remained largely unknown outside of medical science but has been the primary source of cellular tissue for scientific research since 1951 is the story of how Dr. Brian Storrie at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock, and scientists worldwide, have been able to conduct research on key parts of the human cell.

Storrie told his story to students in Jill Carson’s 10th grade English classes at Hope High School here Wednesday as they discussed “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks.”

Lacks was a Black tobacco farmer whose cells from a cervical cancer were harvested without her knowledge in 1951 as the basis for research that has led to the development of polio vaccine, cloning, gene mapping, in virtro fertilization, and other aspects of cellular-based medical science.

Lacks’ story is told in the book “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks,” by Rebecca Skloot, which Carson’s classes have been studying. Carson said the novelized treatment of the story presents relevant cross-discipline context for her students.

“It’s about medical research, civil rights, and the fact that her family didn’t know her cells had been taken; the struggle that her family faced,” Carson said.

Dr. Storrie readily acknowledged the ethical questions which the story of the “HeLa” cells have raised for medical research.

“Cellular research worldwide relies upon these cells,” Dr. Storrie explained. “Cancer cells don’t die; so, they are perfect for research.”

Cellular division (mitosis) occurs within a complete generational cycle every 24 hours in the human body, he said. Consequently, by introducing the cells from Lacks into a nutrient-rich host inside special containers in a sterile environment, the cancer cells from her body continue to reproduce outside of her body.

“That’s why they are called ‘immortal’ cells,” Storrie said.

Based upon the students’ readings in “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks,” they learned that Lacks, from rural Clover, Va., was a patient in the “colored” ward of John Hopkins Hospital in the 1950s, and that, after her death, her cells were illegally sold for research.

In an excerpt from the book, Skloot, the author details how Lacks’ husband refused to sign a waiver to allow his wife’s cervical cells to be harvested; and, how the family felt angry and betrayed at the eventual discovery of the illegal removal of those cells.

That, Skloot noted, was in the 1950s.

“I’m pretty sure that she – like most of us – would be shocked to hear that there are trillions more of her cells growing in laboratories now than there ever were in her body,” Skloot wrote.

Dr. Storrie explained the process by which “HeLa” cells are distributed worldwide, and the students responded by questioning the ethics of modern-day cellular patenting. Storrie noted that cellular patents have a legal foundation in federal case law.

“But, the companies that own them would much rather have the FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration) approval than the patent,” he said.

FDA approval allows the medications and treatments developed from cellular patents to become commercial in the United States, he said.

Storrie, who holds a doctorate from the California Institute of Technology, is a faculty professor of physiology and biophysics at UAMS in Little Rock. His research into the impact of certain proteins upon the organization of cells has relied upon the use of “HeLa” cells, a sample of which he brought to Carlson’s class Wednesday for her students to examine.